To talk about coverage of Africa’s cultural, social and political movements of the 20th century is to talk about the magazine Drum. And the editorial and fashion work of photographer James Barnor — on view through Oct. 15 at the Detroit Institute of Arts — is squarely at the center.

It can be difficult to explain Drum’s importance in Africa in the Fifties and Sixties; for Americans, the closest analogy might be Life magazine, in the scope of subjects. But Drum was much more; for one thing, it had a strong political point of view during the turbulent years as Africa fought for its independence and a new generation of widely photographed media-savvy global leaders emerged.

Drum was a voice and a force, and Barnor’s association with it brought his images to millions of avid readers.

Founded in South Africa in 1951, the magazine was initially titled The African Drum and intended as a lifestyle magazine for white South Africans. It struggled to be successful until a financier named Jim Bailey bought it, dropped “African” from the name, and rebranded it to appeal to the emerging Black middle class1 with an editorial team that knew what mattered to them. From then on, Drum focused its coverage on Black African culture, openly supporting Pan Africanism and its rejection of Western culture and building up Black voices in South Africa and elsewhere as the magazine grew within Africa and then internationally.

In 1950s and ‘60s South Africa, apartheid was a fact of daily life, and Drum played a role in the resistance against the National Party and its oppressive policies. Bailey, along with journalists including Can Themba, Lewis Nkosi, and Todd Matshikiza, exposed life under apartheid and documented the experiences of the oppressed. One of Drum’s most iconic moves was publishing an article by journalist Nat Nakasa, which detailed the Defiance Campaign of 1952, led by Nelson Mandela and Walter Sisulu. Drum was there to report on the struggles and triumphs of the anti-apartheid movement, and the Sharpeville Massacre in 1960, where 69 people peacefully protesting South Africa’s pass laws were killed outside a police station.

James Barnor, National Liberation Movement political rally, Kumasi, 1956 (printed 2010-20). Gelatin silver print. Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière, Paris.

As its popularity grew, Drum opened satellite offices throughout Africa, including one in Accra, Ghana’s capitol. Barnor began freelancing for Drum in 1952, a year before he founded his landmark studio, Ever Young. That association continued, in Ghana and then in London, until 1967.

In Ghana, Barnor’s work for Drum was largely focused on covering current events. Then, in the late 1950s, Barnor moved to London to study color photography technology, which was rapidly replacing black-and-white. By then, Drum had opened a London office. With his keen eye for street style and his new skills with color photography, Barnor chronicled the intersection of the Swinging Sixties and London’s rapidly growing African community, snapping everything from stylish young people on the street to moments of daily life.

James Barnor (Ghana, b. 1929). Independence Celebrations: arrival of American Vice President Richard Nixon, Accra, 1957 (printed 2010–20). Gelatin silver print. Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière, Paris.

© James Barnor, courtesy Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière, Paris.

The relationship between photographer and magazine was, in the end, symbiotic. Drum gave Barnor a massive audience and the prestige of being associated with the magazine that was capturing the moment; Barnor gave Drum some of its most striking and memorable images.

To learn more about Barnor’s work for Drum, visit James Barnor: London / Accra—A Retrospective, on view at the Detroit Institute of Arts through Oct. 15, 2023.

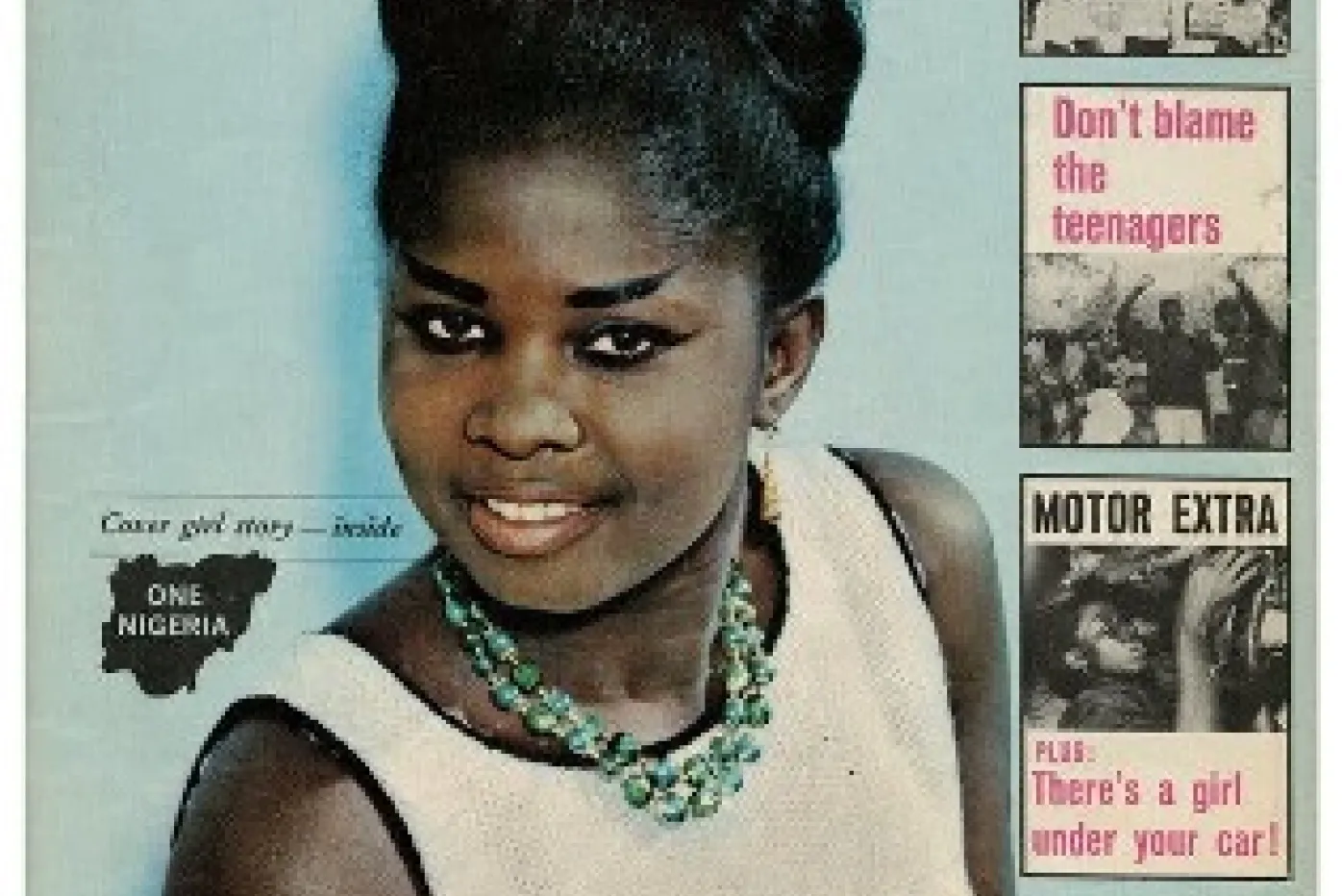

James Barnor, Drum magazine cover with model Marie Hallowi, Kent 1966 (printed 2010-20). Chromogenic print. Autograph, London.