In the 2006 exhibition catalog Snap Judgements: New Positions in Contemporary African Photography, the late Nigerian curator Okwui Enwezor wrote that the act of photographing Africa has been fraught with conflict, particularly “between how Africans see their world and how others see that world…[representing a] clash of lenses…one intensely absorbed in its social and cultural world, [and] the other passing through it.” Who’s photographing who and why? It is a critically important question in the world of photography, particularly when photographers as storytellers shape narratives around culture, history, and those who take part in it and when the narratives are created and promoted by outsiders. Prior to independence from colonial rule in countries throughout Africa (Ghana was the first African country to gain independence from British rule in 1957), representations of Africans as seen in magazines, newspapers, and other publications were largely made by white photographers for American and European audiences. But as photographic practice grew, particularly in West Africa, Black photographers got behind the camera to photograph their people and tell their stories for themselves and for the world.

James Barnor (Ghana, b. 1929). National Liberation Movement Political Rally, Kumasi, 1956. Gelatin silver print. Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière, Paris. © James Barnor, courtesy Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière, Paris.

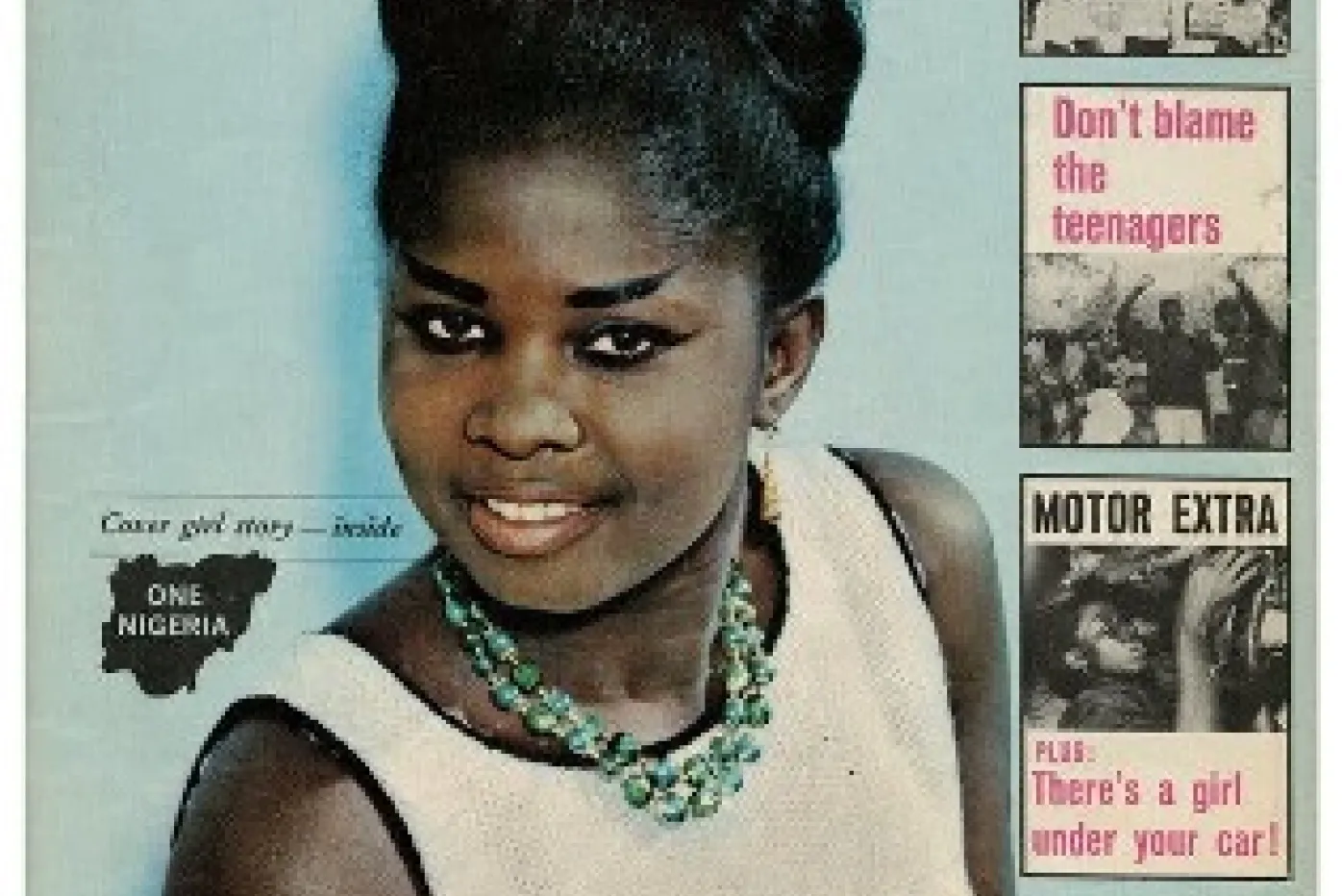

While traveling to Paris for an art fair in 2007, I saw the work of Ghanaian photographer James Barnor (born 1929) for the first time—a stunning, larger-than-life color print of Nigerian model Marie Halowi, who he had photographed in the 1960s for the South African magazine Drum. It wasn’t until 2019 that I had the good fortune to meet James in person with my DIA colleague and Curator of African Art Dr. Nii Quarcoopome who provided an introduction. We spent an afternoon looking through flat files filled with Barnor’s photographs that are housed at his archive in the Paris office of Galerie Cleméntine de la Féronnière. I learned that day what a remarkable artist and human being James Barnor was, and continues to be, as he shared stories about his life, work, friends, family, and historical figures he photographed during his decades-long career in his homeland of Accra, Ghana, as well as in the UK—primarily London, where he lived from 1959–69.

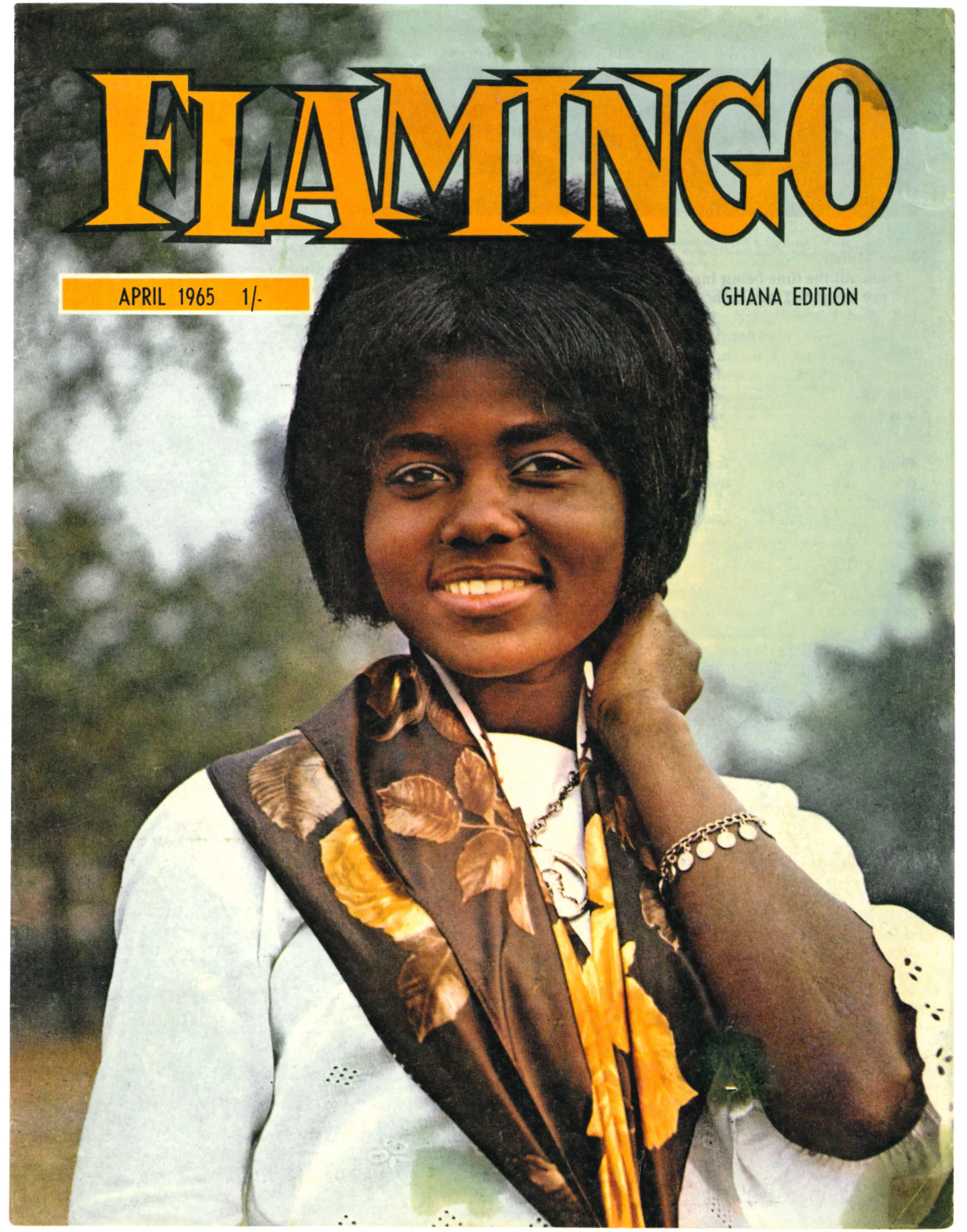

Cover of Flamingo magazine featuring Sarah Mills Okaikoi photographed by James Barnor, April 1965.

Barnor’s career began in the late 1940s when he apprenticed for his cousin, the photographer J.P. Dodoo. In 1952, he branched out into photojournalism when he received an offer to work for The Daily Graphic Ghana’s daily newspaper. Barnor witnessed firsthand as a photographer, the events and people that marked everyday life in Accra as well as those who fought for and eventually achieved independence from British rule in 1957. In the early 1950s, he struck out on his own as a portrait photographer and established the Ever Young studio in 1953. After moving to London in 1959, Barnor attended Medway College of Art and worked regularly for the African magazines Drum and Flamingo where his photographs appeared on their covers and in feature stories showing the lifestyles, fashion, and beauty of young women from the African diaspora. Eventually, he learned color photographic processes which, in 1969, he brought back to Accra when he returned to his homeland where Barnor ran a color lab until 1973. He continued with portrait work and commercial assignments until about 1980, when turned his attention to promoting and supporting Ghanaian musical performers.

James Barnor (Ghana, b. 1929). Sick-Hagemeyer Shop Assistant, 1970. Chromogenic print. Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière, Paris. © James Barnor, courtesy Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière, Paris.

James Barnor (Ghana, b. 1929). Photoshoot of Musician, Salaga Market, Accra, c.1974–76. Gelatin silver print. Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière, Paris. © James Barnor, courtesy Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière, Paris.

The DIA is pleased to present the first major retrospective of James Barnor’s photography in the US. Organized by the Serpentine Galleries, London, the exhibition includes over 150 black-and-white and color photographs from his archive of over 32,000 images, taken from 1950 through 1980. The exhibition opens a window for visitors to witness Barnor’s life and work, and the beauty, history, and vibrancy of the world as seen through his eyes.

- Nancy Barr, James Pearson Duffy Curator of Photography at the DIA