When you think of Native American art, what comes to mind? Maybe birchbark woven into a sturdy basket, colorful beadwork stitched onto leather, or ornately carved totem poles. These forms highlight techniques and materials that have been used by Native American artists for generations. And yet, they tell only part of the story.

Native American art is often viewed as something from the past—something you see behind glass in a museum. But Native American artists are creating powerful, innovative work today, in both historic and contemporary styles. So, let’s expand our sense of what Native American art is—and what it can be.

What about a photograph of Iggy Pop, shirtless and sweaty, howling into a microphone? A stone sculpture? A vibrant abstract painting? A runway-ready dress? These describe just a few of the more than 90 works featured in the Detroit Institute of Arts’ upcoming exhibition Contemporary Anishinaabe Art: A Continuation.

Here, Denene De Quintal, PhD, the DIA’s Associate Curator of Native American Art, shares how visitors can approach the exhibition with an openness to seeing how Anishinaabe artists are shaping Native American art today. The show will be on view from September 28, 2025, to April 5, 2026.

Marcella Hadden (Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe), Jingle Dress, 2020. Courtesy of the artist

What inspired the Detroit Institute of Arts to organize this exhibition?

The DIA has not hosted a major exhibition of Native American art in over 30 years. Before I joined the museum, there hadn’t been anyone in my position for more than a decade. When I started, there were several offers on the table for potential exhibitions, but I told the director that the first exhibition needed to focus on Anishinaabe artists. He agreed that it was an important and meaningful way to start. We were also approached by Anishinaabe artists requesting the very same thing. Those two ideas coincided, and that’s how this exhibition came to fruition.

This exhibition was guided by an advisory committee of Ojibwe, Ottawa, and Potawatomi artists. How did that collaboration shape the show?

It was foundational. We held multiple meetings with the Anishinaabe advisory committee throughout the year, including an in-person visit to the museum. From the beginning, they helped shape the exhibition’s themes, the selection of artworks, and the design and programming.

One of their most meaningful contributions was emphasizing the importance of including Anishinaabemowin (the Anishinaabe language) in the exhibition. As a result, all label copy is translated, highlighting the fact that the language continues to thrive—and encouraging others to learn it.

Another key difference in our process was how the themes developed. Instead of starting with a fixed concept and then sourcing works to fit, we invited artists to submit examples first. The committee reviewed the artworks and, through discussion, determined the exhibition’s themes.

What recurring themes or messages are seen across the diverse range of artists and media?

Many of the works connect through themes like Water Continues, Nature Continues, and Continuing for Generations. These recurring ideas help organize the exhibition into distinct sections, each offering a different lens on Anishinaabe experiences and creativity.

One important section focuses on design. Anishinaabe designers — both in fashion and jewelry — are at the forefront of their fields, yet many people aren’t aware of their presence on major runways.

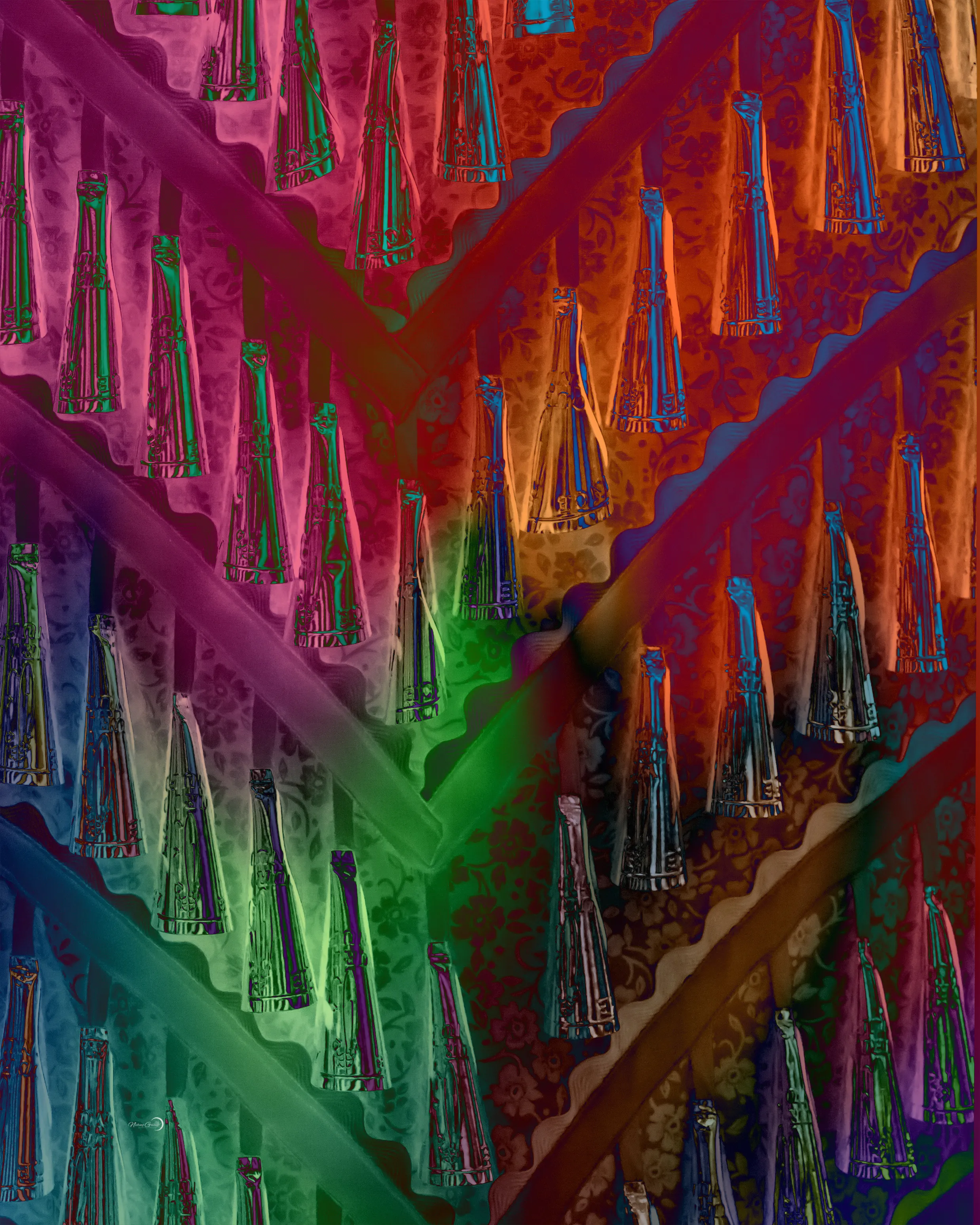

Moira Villiard (Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa), The Waters of Tomorrow, 2019. Courtesy of the artist

Contemporary Anishinaabe Art challenges common perceptions about Native American art. What are some of those outdated assumptions, and how does this show push back?

I think it was said best by one of our advisors that “often Native American art is put in a box of what it can be and what it should be.” There’s often an expectation that Native American art should look a certain way — featuring landscapes, animals, or specific materials — and that it should come from particular regions, especially the Southwest or the Plains. Many people still imagine Native American communities as existing only in the past or in remote places, and not as part of contemporary culture. With this exhibition, there’s an opportunity to put away those preconceived notions.

For example, I recently discussed a work that featured a Marvel superhero, and someone questioned how that could be Native American art. Sometimes people forget that Native American artists are living and creating today — in cities, in diverse communities, across media — and their work reflects that.

Photography is one area where this shift is especially visible. Historically, Native people were often the subjects of photos taken by white photographers, which contributed to stereotypes. In this show, we feature multiple Native photographers presenting their own perspectives — of their families, homes, and lifestyles.

One of them is David Dominic, a well-known photographer of the rock scene in the Detroit area. When we talked about his work for this show, I specifically asked to include his punk photography, because it challenges expectations of what Native American art looks like. One of David’s images features Iggy Pop, and it invites viewers to ask, “Why is this here?” That question opens the door to a broader understanding — one shaped by the artist’s own voice and lived experience.

With over 60 featured artists — and more than 90 works — how did the museum go about selecting the works and voices included?

It was a long and thoughtful process. I was given an initial list of potential artists, which I reviewed and added to based on my own knowledge of the field. We then sent invitations to those artists, and in some cases, those invitations were shared with others — so what began as a targeted outreach became more of an open call.

From there, we had a much larger pool of artists than we could ultimately include. As curator, I approved of the final selections, working closely with the advisory committee who helped shape the vision and focus of the exhibition. The decisions weren’t based on merit alone — many outstanding artists couldn’t be included simply because their work didn’t fit the vision the advisory committee had for the exhibition.

Is there a piece in the exhibition that’s especially meaningful to you? Why?

As a curator, I always joke that we’re not supposed to have favorites — and in this case, I truly don’t. All the artworks in this exhibition are phenomenal. Originally, we planned to feature about 40 works, but once we saw the quality and breadth of what was submitted, we knew we had to include more. The artists really went above and beyond — some even created new pieces specifically for the exhibition.

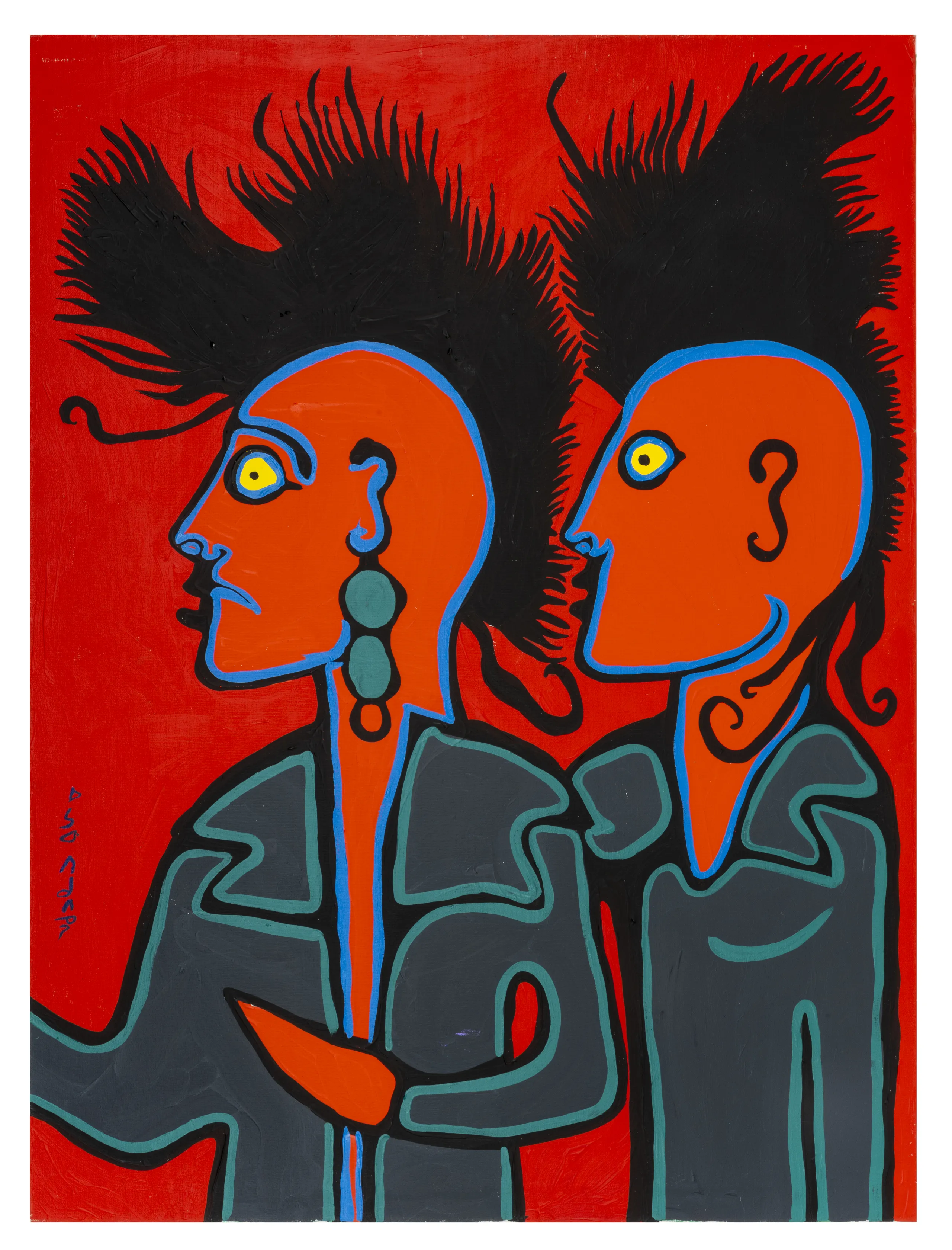

Visitors might be surprised by the range of work on view. For example, we feature three pieces by Norval Morrisseau, one of the most popular artists in the DIA’s collection. Seeing the variety within his work is powerful. We also highlight artists like Kelly Church whose basketry is seeped in cultural traditions, but her inclusion of a QR-Code grafts her in the present, and photography by Richard Church, Kelly’s uncle.

Norval Morrisseau (Bingwi Neyaashi Anishinaabek First Nation), Punk Rockers Nancy and Andy, 1989. The Estate of Norval Morrisseau

What do you hope visitors walk away with after seeing this show?

I hope visitors leave with a new understanding and appreciation for Native American art — especially Anishinaabe art. I want them to recognize that many of these artists are people they may live near, work with, or have gone to school with. I also hope they take away something about Anishinaabe culture, maybe even a few words in the language, and remain open to experiencing contemporary Native American/Anishinaabe art in new ways.

How can institutions like the DIA continue to support and amplify Indigenous voices beyond exhibitions?

While this exhibition is on view for six months, our commitment goes well beyond that. Under the director’s leadership, the DIA has made it a priority to continue to highlight and acquire both historical and contemporary Native American art. It’s important that visitors see not only the deep history of Native American art but also its ongoing impact. The theme of continuation is central to the exhibition and reflected throughout the museum.

We're also amplifying Anishinaabe voices through programming. One highlight is a screening of Star Wars dubbed in Anishinaabemowin. For another program, we’ll host a celebrated Anishinaabe author in partnership with a local Native American community center. We hope that these projects will form the foundation for a continuation of this work in Detroit Native American communities and beyond.