From the Director, September 2019

Updated Jul 20, 2022

In honor of Robert S. Duncanson

Over Labor Day weekend, while I was preparing this newsletter, I read the fascinating life story of the African American 19th century painter, Robert S. Duncanson. I was especially interested in his trip to Europe during the 1860s, to learn the great art of the British, Italian and French masters. Other fellow American artists, like Frederic E. Church, made similar trips during this time. However, in an era where many black Americans were still enslaved, Duncanson had the rare opportunity to travel, thanks to the sponsorship of an abolitionist organization from Ohio.

He learned while in Europe, and was highly praised by the public and the European aristocracy that he met in England, who considered him one of the great American landscape painters of his time. Apparently, one of his fervent admirers was the American actress, Charlotte Cushman, very famous on her own right as a cross-dressing tragedienne and pioneer of feminism, who was also in England at the time Duncanson visited. Cushman, who was very well connected socially, introduced the artist to the King of Sweden, Charles XV, and brought him into Duncanson’s studio in London. The King was not only very supportive of the arts but also an amateur painter himself. During that visit, Charles XV acquired one of the artist’s most famous paintings, Land of the Lotus Eaters, which today is still kept in the Royal Swedish collection.

As I have mentioned on other occasions, because of my studies of European art, my knowledge of African American art is, unfortunately, limited, but it has been growing since moving to Detroit and working at the DIA. Over time I have become passionate about this chapter of the history of art, and I can only imagine what conversations might have occurred between an amateur painter King, a feminist actress and an artist of color in front of the Land of the Lotus Eaters in London in the 19th century.

These kinds of stories and many others can be relived in our galleries, where we display five works by Duncanson. The first one to enter our collection in 1944 was the Drunkard’s Plight, almost a hundred years after the artist painted it (1845). Perhaps his most famous work at the DIA is the landscape Ellen’s Isle, Loch Katrine, which is prominently on view in our American wing. I encourage everyone to see this masterpiece at the DIA. It has a very similar quality and beauty as the Land of the Lotus Eaters – the abovementioned work that the King of Sweden acquired in London. You will enjoy the inspiring atmospheric effects of the sunlight filtered through the clouds, then reflected on the water in the most idyllic and peaceful natural setting. It is a good image to admire alone or with friends, helping us decompress from our sometimes too-stressful lives.

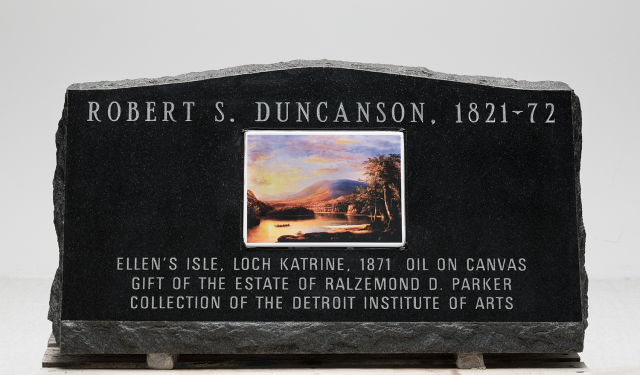

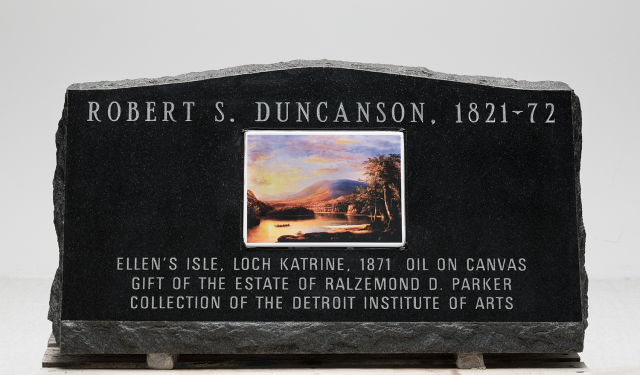

If you decide to pay homage to this painting you will also see Duncanson’s tombstone installed in the gallery. The artist passed away 147 years ago and was buried in an unmarked grave on the family plot at the Historic Woodland Cemetery in Monroe, Michigan, where his relatives had roots as carpenters. The DIA unveiled the tombstone last June in a ceremony that celebrated Duncanson as well as local artist Dora Kelley and the Detroit Breakfast Club, who led this initiative and raised the funding to carve the tombstone. It beautifully features DIA’s painting Ellen’s Isle, Loch Katrine one side, and a portrait of the artist and a quote from him on the other.

The tombstone will be on view at the DIA until November when it will be placed on Duncason’s grave, now marked and honored, after the opening of our upcoming exhibition, Detroit Collects, Selections of African American Art from Private Collections – a show that celebrates African American art and culture in Detroit.

It is very inspiring to see the museum as a platform where the communities can express themselves, learn and share life experiences, and help improve our society. As we recognize Duncanson, we added a much-needed chapter to his life, bringing all of us together to remember that the errors of the past are opportunities to improve our present, and secure a better future for all.

DIA Director, Salvador Salort-Pons in Rivera Court

In honor of Robert S. Duncanson

Over Labor Day weekend, while I was preparing this newsletter, I read the fascinating life story of the African American 19th century painter, Robert S. Duncanson. I was especially interested in his trip to Europe during the 1860s, to learn the great art of the British, Italian and French masters. Other fellow American artists, like Frederic E. Church, made similar trips during this time. However, in an era where many black Americans were still enslaved, Duncanson had the rare opportunity to travel, thanks to the sponsorship of an abolitionist organization from Ohio.

He learned while in Europe, and was highly praised by the public and the European aristocracy that he met in England, who considered him one of the great American landscape painters of his time. Apparently, one of his fervent admirers was the American actress, Charlotte Cushman, very famous on her own right as a cross-dressing tragedienne and pioneer of feminism, who was also in England at the time Duncanson visited. Cushman, who was very well connected socially, introduced the artist to the King of Sweden, Charles XV, and brought him into Duncanson’s studio in London. The King was not only very supportive of the arts but also an amateur painter himself. During that visit, Charles XV acquired one of the artist’s most famous paintings, Land of the Lotus Eaters, which today is still kept in the Royal Swedish collection.

As I have mentioned on other occasions, because of my studies of European art, my knowledge of African American art is, unfortunately, limited, but it has been growing since moving to Detroit and working at the DIA. Over time I have become passionate about this chapter of the history of art, and I can only imagine what conversations might have occurred between an amateur painter King, a feminist actress and an artist of color in front of the Land of the Lotus Eaters in London in the 19th century.

These kinds of stories and many others can be relived in our galleries, where we display five works by Duncanson. The first one to enter our collection in 1944 was the Drunkard’s Plight, almost a hundred years after the artist painted it (1845). Perhaps his most famous work at the DIA is the landscape Ellen’s Isle, Loch Katrine, which is prominently on view in our American wing. I encourage everyone to see this masterpiece at the DIA. It has a very similar quality and beauty as the Land of the Lotus Eaters – the abovementioned work that the King of Sweden acquired in London. You will enjoy the inspiring atmospheric effects of the sunlight filtered through the clouds, then reflected on the water in the most idyllic and peaceful natural setting. It is a good image to admire alone or with friends, helping us decompress from our sometimes too-stressful lives.

If you decide to pay homage to this painting you will also see Duncanson’s tombstone installed in the gallery. The artist passed away 147 years ago and was buried in an unmarked grave on the family plot at the Historic Woodland Cemetery in Monroe, Michigan, where his relatives had roots as carpenters. The DIA unveiled the tombstone last June in a ceremony that celebrated Duncanson as well as local artist Dora Kelley and the Detroit Breakfast Club, who led this initiative and raised the funding to carve the tombstone. It beautifully features DIA’s painting Ellen’s Isle, Loch Katrine one side, and a portrait of the artist and a quote from him on the other.

The tombstone will be on view at the DIA until November when it will be placed on Duncason’s grave, now marked and honored, after the opening of our upcoming exhibition, Detroit Collects, Selections of African American Art from Private Collections – a show that celebrates African American art and culture in Detroit.

It is very inspiring to see the museum as a platform where the communities can express themselves, learn and share life experiences, and help improve our society. As we recognize Duncanson, we added a much-needed chapter to his life, bringing all of us together to remember that the errors of the past are opportunities to improve our present, and secure a better future for all.